Maintenance

Boats require a rigorous maintenance routine. Keeping up with boat maintenance is critical to improving performance and preventing repairs. We have expert information on maintaining and repairing everything from heads to hulls.

Decked Out

Decked Out The inside track on replacement flooring Boat decks aren’t often treated favorably. Sunscreen, saltwater, beer, potato chips, motor...

Read moreDetailsSolar Panels for your Boat

Free Energy The lowdown on solar panel selection and installation Sunshine and boats are a natural together, so why not...

Read moreDetailsAnchoring in the Bahamas

Anchoring in the Bahamas Tips to safely anchor without disrupting your surroundings Ahhh…anchored in the Bahamas. Your cruising dream for...

Read moreDetailsTroubleshooting Your Boat’s Air-Conditioning System

Cool and in Control Learn what to do when the air conditioner stops working. Ah, paradise. You have traveled to...

Read moreDetailsHow to Clean Vinyl Boat Seats

Clean That Vinyl Take precautions before seats stain. A friend purchased a used center console that was in really good condition....

Read moreDetailsGalley hacks to keep the party going

Entertaining Emergencies Galley hacks to keep the party going no matter what fails You have invited a half-dozen folks to...

Read moreDetailsFrom the Beginning – History of Southern Boating

From the Beginning Southern Boating’s DIY roots In September 1972, Volume 1, Number 1 of Southern Boating magazine appeared on...

Read moreDetailsDIY: Picking the Right Spotlight

Under the Spotlight Bright ideas for selection and installation By Frank Lanier, Southern Boating 2021 Spotlights are one of those...

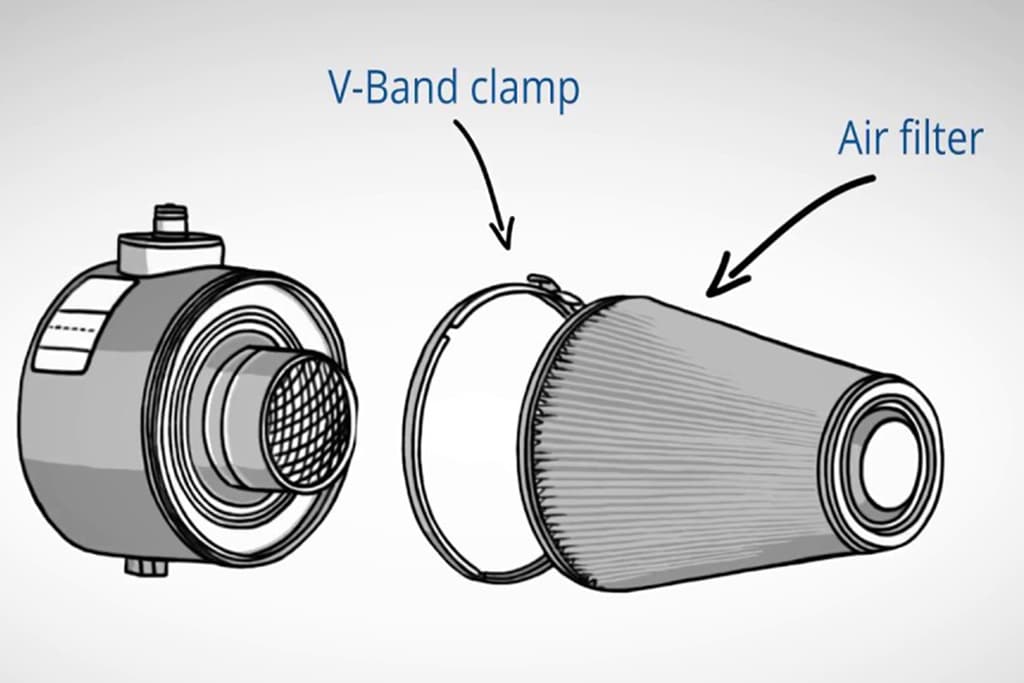

Read moreDetailsServicing Walker AIRSEP® Air Filters Video Series

Walker AIRSEP Air Filters are designed to keep down noxious gas and oil mist on turbocharged diesel engines. Check out...

Read moreDetailsWashing Down Your Boat

Wash It Down Plan out the necessary steps before installing a deck wash down system. By Frank Lanier, Southern Boating...

Read moreDetailsBoat Coating Controversy

Coating Controversy Wax? Plastic polymers? Ceramic coatings? What’s the deal? Mother Nature is brutal on boats. Sun, wind, water, and...

Read moreDetailsHow to Install LED Lights on Your Boat

How to Install LED Lights on Your Boat When you install LED lights on your boat, you'll boost the mood...

Read moreDetailsUpgrading Your Dashboard? What You Need to Know

Upgrading Your Dashboard Before buying new electronics, make sure you can upgrade your dashboard. If your display screens freeze up...

Read moreDetailsHow to Wire a T-Top

How to Wire a T-Top Here's how to wire a T-Top and free up console space. While there never seems...

Read moreDetailsHow to Install a Solar Panel on Your Boat

Install a Solar Panel on Your Boat Sunbathers delight! Here's how to install a solar panel on your boat. It’s...

Read moreDetails