Maintenance

Boats require a rigorous maintenance routine. Keeping up with boat maintenance is critical to improving performance and preventing repairs. We have expert information on maintaining and repairing everything from heads to hulls.

DIY Gelcoat

DIY Gelcoat Gelcoat care, protection and minor repair of this finish are essential to your boat’s maintenance. Here's the lowdown on DIY...

Read moreDetailsAnnual Haul Out Guide

A Southern Boating Magazine Supplement: Annual Haul Out Guide Our annual haul out guide has everything you need to know...

Read moreDetailsFive Ways to Cut Down on Amp Usage

Five ways to cut down on amp usage Most modern marine equipment has evolved to require much less power....

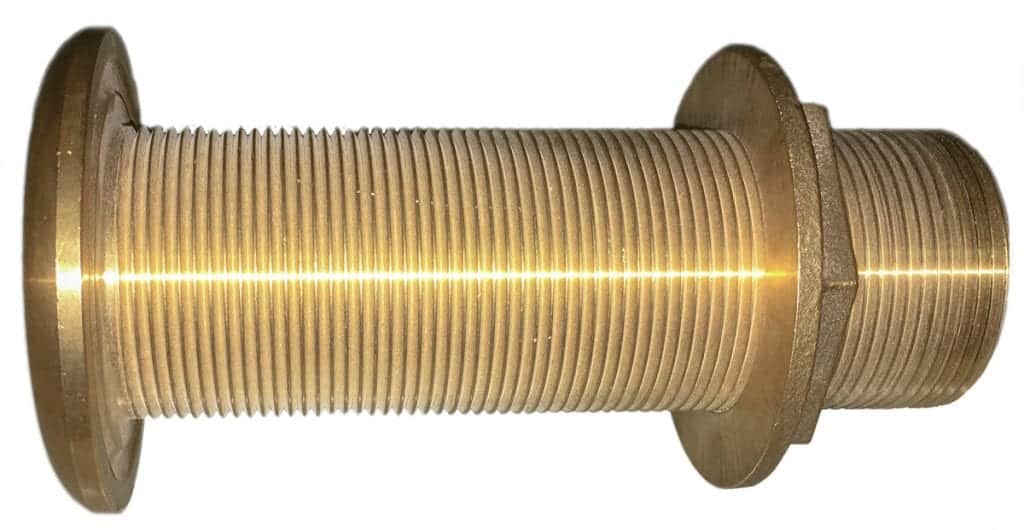

Read moreDetailsBoats and Thru-hull Holes

When you have to install thru-hull holes, do it right the first time. Most any boat maintenance guru worth his...

Read moreDetailsSacrificial Anodes

Sacrificial Anodes Sacrificial anodes die so your underwater gear may live. A war is raging under your boat. High-priced running...

Read moreDetailsInstall a Stereo on Your Boat

Install a Stereo on Your Boat Everyone likes tunes while on the water, but if your boat didn’t come with...

Read moreDetailsDock Maintenance

Dock Maintenance Regular dock maintenance will keep it safe for your boat and guests. It wouldn’t be wrong to say...

Read moreDetailsSynthetic Teak

New synthetic teak decking keeps feet cooler. The beauty of real teak wood on boat decks is undeniable, but look-alike...

Read moreDetailsReplace Your Enclosures

Replace Your Enclosures Blurry or worn view? It may be time to replace your enclosures. While under way, if you...

Read moreDetailsWhich Marine Survey Do You Need for Your Boat?

At some point, you'll need a marine survey. We break down the most common marine surveys. Most boat owners will...

Read moreDetailsCheck your Clamps and Hoses

Check your clamps and hoses before they check out. Hard slams and big bangs are conditions every mariner endures in...

Read moreDetailsPlanning Your ICW Trip

Take the time to enjoy the road less traveled when planning your ICW trip. When it comes to cruising the...

Read moreDetailsSecurity Tips For Your Boat

Thief-proof your boat with these security tips While most folks envision Black Beard or Captain Kid when marina Tiki-bar talk turns...

Read moreDetailsVinyl Boat Wraps

Vinyl Boat Wraps Protect your boat’s hull in a variety of colors and designs with the use of creative vinyl...

Read moreDetailsHow to Install a Transom Shower on Your Boat

Install a transom shower to rinse away the sand, cool off from the hot sun and wash away the salt....

Read moreDetails