Maintenance

Boats require a rigorous maintenance routine. Keeping up with boat maintenance is critical to improving performance and preventing repairs. We have expert information on maintaining and repairing everything from heads to hulls.

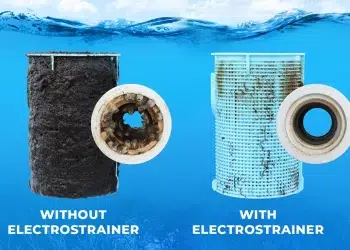

Prevent Marine Growth In Your Pipework With ElectroStrainer

ElectroStrainer: The Smart Technology Defending Boats Against Marine Growth It’s easy to see barnacles and biofouling on the hull of...

Read moreDetailsMaintaining Boat Freshwater Systems: A Sure Way To Stay Cool

A Guide to Boat Freshwater System Maintenance Keep it flowing fresh on deck. When it's HOT there’s only one thing...

Read moreDetailsTrim Tab Maintenance Guide: Ensuring a Ride You’ll Love

Take care of the systems on board for a smooth ride. Today’s trim tabs are not the trim tabs from...

Read moreDetailsLife Raft Readiness: A Comprehensive Maintenance and Inspection Guide

Ready to Launch Life raft inspections and stowage Like bear pepper spray and supplies for the zombie apocalypse, life rafts...

Read moreDetailsIt’s A Boat Decking Revolution: Improvements For Extra Comfort & Safety

The latest synthetic boat decking is rugged, simple to clean, and easy on the feet. Most boaters have a love-hate...

Read moreDetailsStay Afloat with Easy Bilge Pump Maintenance: Tips and Tricks

Bilge Pump Maintenance Keep the bilge area clean and test the pump to make sure it is working. Dewatering device—that’s...

Read moreDetailsA High Quality Water Heater Creates a Comfortable Boating Experience

Hot Water Aboard! Easy ways to raise your boat’s water temperature.At the end of a wonderful day aboard, a hot...

Read moreDetailsExpert Boat Refit Advice: Know What You’re Getting Into

Choosing to Refit is Not a Simple Decision Know what you’re getting into before deciding to do a refit. The...

Read moreDetailsWhat To Look For When You Need A Boat Yard

Yard Work What to look for in a yard when it’s time to do some serious work on the boat....

Read moreDetailsNew Boat for Less

New Boat for Less Find joy in buying a used boat by keeping your goals in focus. Daydreaming of a...

Read moreDetailsScanning your Engine Temperature

Engine Scan Keep an infrared thermal device in your onboard toolbox to check engine temperature and more. Finally, a long-awaited...

Read moreDetailsTroubleshooting Tilt and Trim

Optimize Performance Troubleshooting outboard tilt and trim problems Failure of your boat’s tilt and trim feature will affect all phases...

Read moreDetailsInstalling a Bow Thruster

DIY - Installing a Bow Thruster You found a used boat that has everything to meet your goal—everything but a...

Read moreDetailsHow to Battle Bilge Odors

The Smell of Victory How to battle bilge odors There are many benefits to having a clean bilge. Not only...

Read moreDetailsCorrosion Testing

Corrosion Testing The importance of checking anode consumption While I’ve developed many theories about why and how corrosion occurs aboard...

Read moreDetails