DIY

DIYers you’ve landed in the right place! Our extensive DIY articles will help you tackle any project, big or small. Our expert writers provide comprehensive information to help you troubleshoot problems and work toward preventing future ones.

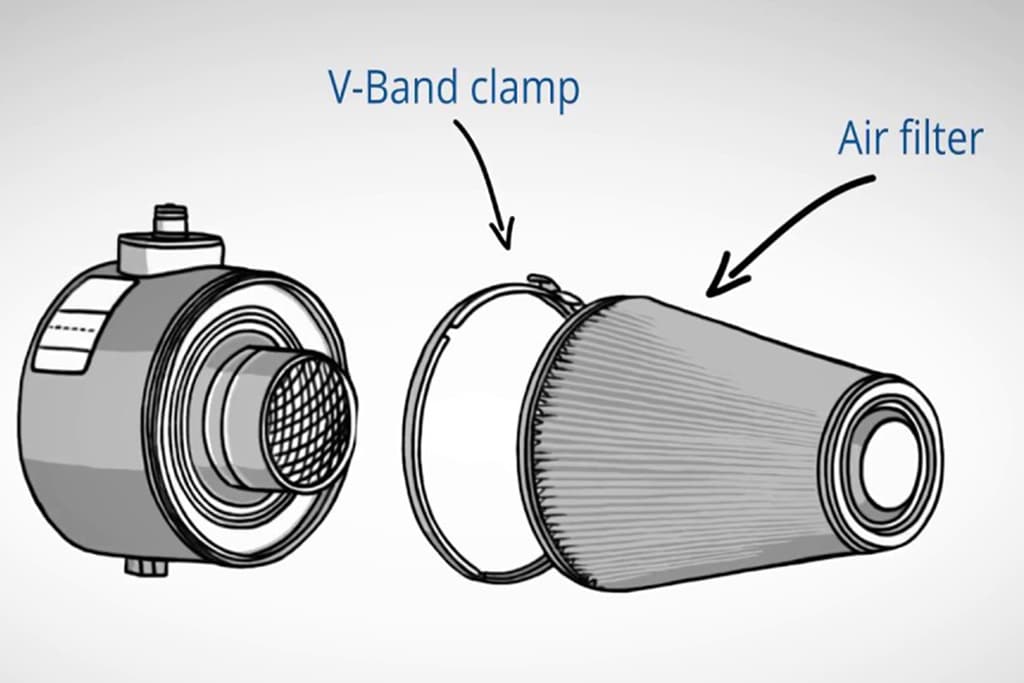

Servicing Walker AIRSEP® Air Filters Video Series

Walker AIRSEP Air Filters are designed to keep down noxious gas and oil mist on turbocharged diesel engines. Check out...

Read moreDetailsWashing Down Your Boat

Wash It Down Plan out the necessary steps before installing a deck wash down system. By Frank Lanier, Southern Boating...

Read moreDetailsBoat Coating Controversy

Coating Controversy Wax? Plastic polymers? Ceramic coatings? What’s the deal? Mother Nature is brutal on boats. Sun, wind, water, and...

Read moreDetailsHow to Install LED Lights on Your Boat

How to Install LED Lights on Your Boat When you install LED lights on your boat, you'll boost the mood...

Read moreDetailsUpgrading Your Dashboard? What You Need to Know

Upgrading Your Dashboard Before buying new electronics, make sure you can upgrade your dashboard. If your display screens freeze up...

Read moreDetailsHow to Wire a T-Top

How to Wire a T-Top Here's how to wire a T-Top and free up console space. While there never seems...

Read moreDetailsHow to Install a Solar Panel on Your Boat

Install a Solar Panel on Your Boat Sunbathers delight! Here's how to install a solar panel on your boat. It’s...

Read moreDetailsDIY Gelcoat

DIY Gelcoat Gelcoat care, protection and minor repair of this finish are essential to your boat’s maintenance. Here's the lowdown on DIY...

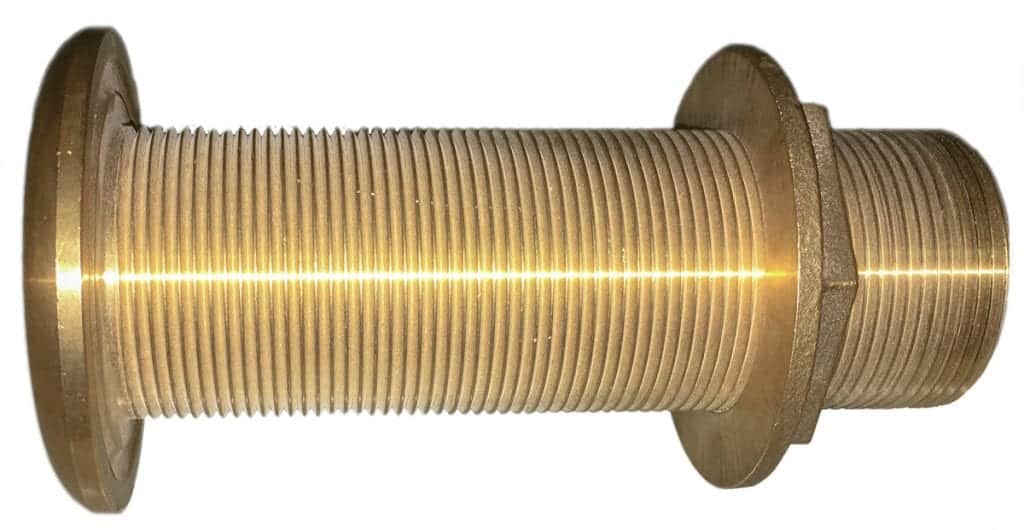

Read moreDetailsBoats and Thru-hull Holes

When you have to install thru-hull holes, do it right the first time. Most any boat maintenance guru worth his...

Read moreDetailsInstall a Stereo on Your Boat

Install a Stereo on Your Boat Everyone likes tunes while on the water, but if your boat didn’t come with...

Read moreDetailsSynthetic Teak

New synthetic teak decking keeps feet cooler. The beauty of real teak wood on boat decks is undeniable, but look-alike...

Read moreDetailsWhich Marine Survey Do You Need for Your Boat?

At some point, you'll need a marine survey. We break down the most common marine surveys. Most boat owners will...

Read moreDetailsPlanning Your ICW Trip

Take the time to enjoy the road less traveled when planning your ICW trip. When it comes to cruising the...

Read moreDetailsSecurity Tips For Your Boat

Thief-proof your boat with these security tips While most folks envision Black Beard or Captain Kid when marina Tiki-bar talk turns...

Read moreDetailsHow to Install a Transom Shower on Your Boat

Install a transom shower to rinse away the sand, cool off from the hot sun and wash away the salt....

Read moreDetails