The Okeechobee Waterway: Cruising the water that connects the seas

Florida is best known to boaters for the water around its edges, which is no wonder with more than 2,000 miles of tidal shoreline open to the sea. But the interior of Florida is almost as wet as its shoreline, with some 30,000 inland lakes covering over 3 million acres.

With all of that water in between and the distance around the state, it didn’t take early residents long to think of connecting the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts by a cross-state waterway. Creating this navigable route was made easier by a huge lake conveniently placed in the southern center of the state—the second-largest lake (behind Lake Michigan) in the contiguous 48 States and the largest contained within a single state. Lake Okeechobee was known to Florida’s Seminole Indians as “Oki Chubi,” which means “Big Water.”

The Waterway’s Origins

In the late 1800s, developers began plans to connect Lake Okeechobee to the headwaters of the Caloosahatchee River. The proposal was to cultivate the land around the lake and create a water-navigable route to the Gulf Coast. The land reclamation program was overwhelmingly successful and opened thousands of acres of rich agricultural property around the lake for settlement. Unfortunately, in the following years, a series of hurricanes exposed those new lake residents to catastrophic flooding and the loss of many lives.

Realizing the need to protect people and property as well as creating a permanent cross-Florida waterway, Florida’s government funded programs to build larger containment dikes around the lake and the “Okeechobee Waterway” as we know it today.

The Route

The waterway was developed by digging two man-made canals—from the headwaters of the Caloosahatchee River on the Gulf Coast and from the St. Lucie River on the East Coast—to Lake Okeechobee. The official length of The Okeechobee Waterway is 156 statute miles or 134.3 nautical miles from its intersection with the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway in Stuart to the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway in Fort Myers. Due to Lake Okeechobee’s shallow depths of 8 to 12 feet, and only averaging 15 feet above sea level, a direct connection to the sea would drain the lake completely.

To maintain the lake’s depth, three locks were built to raise vessels from sea level on the Gulf Coast to the level of Lake Okeechobee, and two locks lower vessels back down to sea level on the Atlantic Ocean. Two established routes cross the lake. Route 1, which is the “Cross Lake Route,” proceeds from Port Mayaca directly across the southern portion of the lake to the town of Clewiston. Route 2 is referred to as the “Rim Route” and follows the southern shoreline passing the towns of Pahokee and Belle Glade before joining up with Route 1 at Clewiston.

Route 1 offers a faster crossing and carries more depth, while Route 2 allows for a more relaxed and protected route, especially with southerly winds.

Navigation and Lock Handling

The specific elevation change of the water in the locks will vary with the depth of the lake. When the lake and canal water levels are high enough, some of the locks may stay open.

During very low water levels, the St. Lucie and Franklin locks may operate on restricted hours to maintain water depth. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) operates the locks and maintains Lake Okeechobee’s depth.

Adhering to the same rules as the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), the Okeechobee Waterway is marked off in statute miles and follows the lateral buoy system of keeping red markers or markers with yellow triangles to starboard when traveling from east to west.

Water depth and bridge clearance are the two factors a boater must take into account when planning a crossing. The waterway’s depth varies with the lake level, so consulting the USACE is important for a safe crossing. In addition to the five locks, there are numerous opening and fixed bridges along the way. The lowest fixed bridge at Port Mayaca allows 49 feet of clearance at high water. Boating through the locks is not difficult with proper preparation. The lock walls are concrete, so having enough durable fenders to protect the boat is important.

The lock tenders will instruct boaters on which side of the lock they want the vessel tied. In locks with rising water, the lock tenders will lower fore and aft handling lines to the vessel. The mariner will take one wrap of the lines around cleats on the craft and take up the slack line as the boat rises.

If possible, it’s best not to be the first vessel in a lock with rising water, as that boat takes the most turbulence of the water coming through the opening in the forward lock gate. When a boat is being lowered in a lock, the handling lines are also wrapped once around a cleat, and the line is allowed to play out as the vessel is dropping.

Always wear sturdy gloves with which to handle the lines. On average, 30 minutes should be allowed to transit each lock. Unless operating on restricted hours during low water levels, the locks open on request daily from 7AM until 5PM. The last entrance to a lock is at 4:30PM. A fast boat averaging 20 knots can complete the crossing in about eight hours. A trawler or sailboat would take around 20 hours at 7 knots, making for a leisurely trip with two nights spent on the waterway in the process.

Stops Along the Okeechobee Waterway

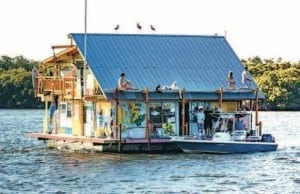

Most boaters will stage at a marina in Stuart on the East Coast or in Fort Myers on the Gulf Coast to begin a crossing. There are marinas and municipal town docks conveniently located for the seafarer willing or needing to take multiple days to cross. Communities like Port LaBelle, Moore Haven, Clewiston, and Indiantown are an interesting part of Florida’s history.

These towns and villages give the visiting mariner a real sense of “old Florida,” where hunting and fishing are still an important way of life. Wilderness outfitters provide guided trips through the beauty of this remote area with fishing or hunting expeditions. The Waterway’s inland protection from coastal storms is also creating a growing business for off-season boat storage, with facilities in Stuart, Indiantown and Port LaBelle, some of which offer large storm-rated buildings where a vessel can be kept indoors.

Florida is a fascinatingly diverse state, with coastal communities influenced by the cultures of all its transplanted citizens and visitors. Central Florida, by comparison, still has much of its original culture and character intact. If the majority of your boating has been offshore, cruising the Okeechobee Waterway not only makes for easy passage from one coast to the other, it also provides for an interesting view of historic Florida and the beauty of water in between.

Cruiser Resources

MARINAS EAST OF LAKE OKEECHOBEE

Indiantown Marina, Indiantown

(772) 597-245 • indiantownmarina.com

River Forest Yachting Centers, Stuart

(772) 287-4131 • riverforestyc.com

Sunset Bay Marina & Anchorage, Stuart

(772) 283-9225 • sunsetbaymarinaandanchorage.com

MARINAS WEST OF LAKE OKEECHOBEE

City of Fort Myers Yacht Basin

(239) 321-7080 • cityftmyers.com/381/Yacht-Basin

Legacy Harbour Marina, Fort Myers

(239) 461-0775 • legacyharbourmarina.com

Moore Haven City Docks

(863) 946-0711 • moorehaven.org

River Forest Yachting Centers, Moore Haven

(863) 612-0003 • riverforestyc.com

Roland & Mary Ann Martins

Marina & Resort, Clewiston

(863) 983-3151 • RolandMartinMarina.com

ATTRACTIONS/GUIDES

Lake Okeechobee Fishing Guide

lakeokeechobeeguide.com

Eaglebay Airboat Rides

okeechobeeairboat.com

Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Seminole Indian Museum

ahtahthiki.com

BlueSeas’ Okeechobee Waterway Cruising Guide

offshoreblue.com/cruising/okeechobee.php

By Bob Arrington, Southern Boating Magazine

July 2017