The year was 1887, and the island was Martinique. I’ve come to the quiet, French-speaking island in the Lesser Antilles to find out if Gauguin’s paradise still exists and, perhaps, to be inspired in the process.

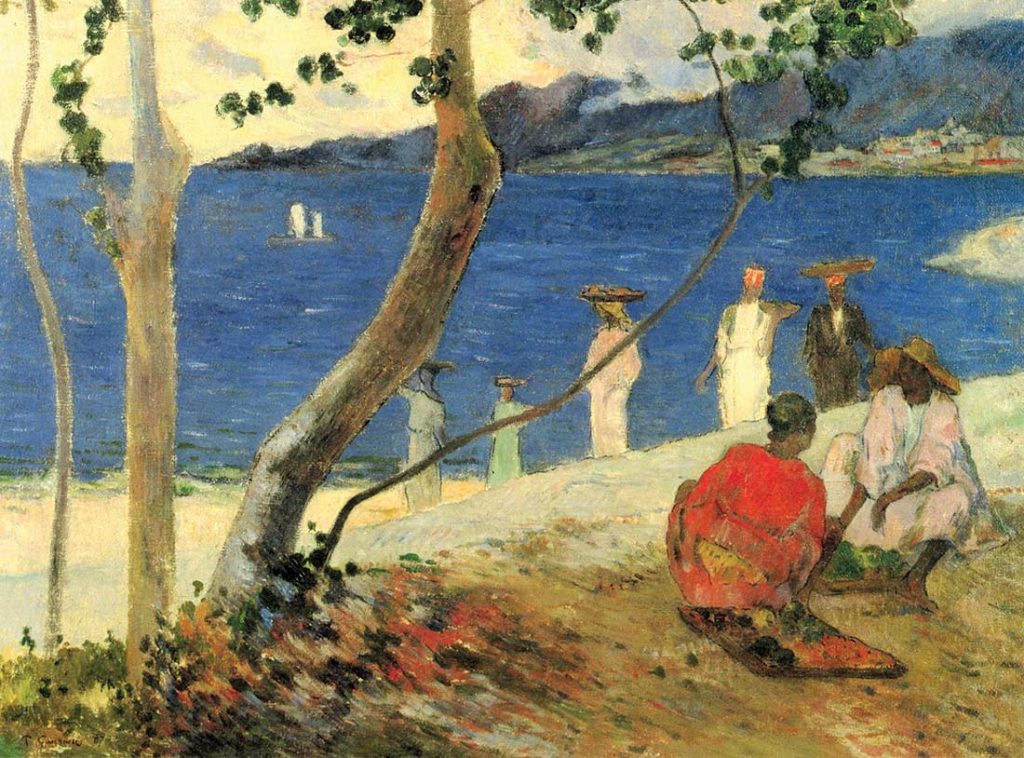

Tahiti wasn’t painter Paul Gauguin’s first love. Long before he made the island a famous paradise in his lush artworks, Gauguin had found another Garden of Eden much closer to home—in the Caribbean.

My quest to find Gauguin’s paradise starts in the hotel-studded south, a modern-day paradise of beaches and palm trees. On this bright afternoon, the sun is high and the lagoons glow like Hopi turquoise. I’m skipping over the shallow water in a speedboat with a famous musician, a pair of Brazilian women in string bikinis and a young local woman with a pink flower tucked behind her ear.

I meet Victor O that morning in the busy town of Le Francois. He’s a young guy with a clean-shaven head; a huge grin cracks his beard. He’s amused by my quest to chase Gauguin’s ghost around Martinique, and local pride inspires him to show me the most beautiful natural swimming pool on the island—Josephine’s Bath. “Joséphine was born on a habitacion beyond the mornes,” Victor says as we slalom through a maze of palmetto-tufted islands. He points at a rumpled range of cane-quilted hills to the west. “She was an island girl, and she was Napoleon’s great love. He made her the Empress. Legend says she would come out here to bathe in the seawater.”

The captain tosses the anchor over a submerged sandbar between two islands. We drink planter’s punch, a homemade brew that’s more rum than punch.

“It’s customary here after the first rum that a bikini becomes a monokini,” one of Frenchmen says as he pours a cup and passes it over. “And of course after two rums, well, then the monokini also goes.”

We leap overboard. The water is so clear and the sun so brilliant that even five feet down the rippled sand warms my soles. “It’s probably just a legend that Joséphine came out here,” Victor laughs. “I’m not sure she could even swim.” Whether the legend is true or not, the pool is idyllic. The Brazilians float on their backs while the progressively emptier bottle of rum punch bobs in the waves.

That evening as shadows creep down the mornes I have dinner with my new friends at Soleil Faire. It’s a romantic spot, a Creole house on a hillside overlooking the Empress’ playground. Waiters snap around in pressed black and candles flicker inside hurricane lanterns. “This is the best table on the island,” purrs the woman with the flower behind her ear. “The chef was trained by Alain Ducasse, himself.”

When the plate is presented, I smile and remember a conversation Victor and I had about food. “In Martinique we are French first and Caribbean second, so you can imagine that food is very important to us,” he’d said. “Our cuisine is truly Creole. We combine the generosity of Africa and the spices of India with French savoir faire. No matter if you eat at a beach shack or a Michelin-starred restaurant, the food is always the same, and that is to say, superb.” I chuckle as I carve into my lacquered pigeon.

I head to downtown Fort de France the next day to track down the only address I have for Gauguin. I have an old sketch of his street. The artist’s connection to Martinique is largely unknown even to locals, which is why I’m lucky to find Marie, a French historian. But even she didn’t realize that Gauguin had an address here in town. We set out to find Rue Victor Hugo #30.

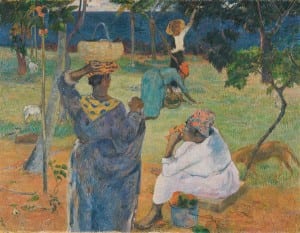

Marie is short but moves quickly in a flowing blue and white dress; I dodge pedestrians to keep up. When she talks, her teeth flash in a frame of shaded purple lipstick. “I love all Gauguin’s colors,” she says as we wend our way through a square where an office building with mirrored windows reflects the beige steeple of Cathedrale St. Louis. “When I was young, I wore lots of colors just like the women in his paintings.”

Brightly dressed women straight out of a Gauguin sashay past in ruffles of red, green, orange, and yellow. “We are the only part of France that still wears folk dress, our Madras,” Marie says. “If you wore traditional dress in Brittany today people would laugh at you. Not here. Here we say, ‘good for you.’”

We find #30 near the end of Rue Victor Hugo where it dead-ends into La Savane Park. The white two-story building is wedged between a jewelry store and an osteopathic office. Sunshine slants down on the afternoon shoppers. Now, just as in the 19th-century sketch, the street is bustling. Gauguin kept #30 as his forwarding address, but he quickly set out to wander the island. I decide to do the same.

It’s during my wanderings that I meet Laurent, a local sculptor and painter. He invites me that night to a party at his villa. Gauguin always claimed to have discovered paradise. In one of his first letters home, he gushed about the luxuriant coast:

“It’s a paradise on the shore of the isthmus. Below us is the sea, fringed with coconut trees, above, fruit trees of all sorts… Nature is at its most opulent, the climate hot, with cool spells intervening. With a little money you can have all that is needed to be happy.”

“Does that Martinique still exist?” I ask the group. “Yes,” Laurent says, pushing his glasses back on his head. “If Gauguin came tonight on the Air France flight, he would find that same beauty, the same colors, the same volcanoes, and sugar cane fields.”

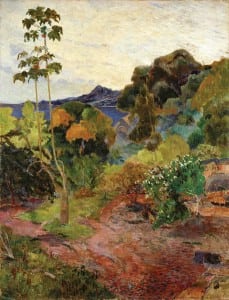

I hitch a northbound ride the next morning, trading the crowded coastal plain for the cooler mountains. The landscape quickly morphs into Gauguin’s Eden. Dense forests crowd overhead and each valley has a small village. The houses all have that lovely state of decay: cracked stucco walls and baked roof tiles furred with moss.

The road eventually slinks below Mount Pelée, and hairpin turns drop us into the rambling town of St. Pierre. When Gauguin arrived a century ago, this port was the most celebrated city in the French West Indies. More than 30,000 people lived here. They promenaded in the latest haute couture from Paris while horsedrawn trams ran along the cobbled streets. The theatre—a replica of the one in Bordeaux—had 1,000 seats. But the town is smaller today with barely 4,000 people. My ride drops me off near the beach where young men build a stage in the shade of sea grape trees. Nearby, women set up food stalls. Every time the sea breeze picks up, their white dresses billow and reveal Madras colors beneath.

One May morning not long after Gauguin left Martinique, Mount Pelée detonated. A nuee ardente (a glowing cloud) exploded down the volcano’s ravines and incinerated St. Pierre and the surrounding villages. Thirty thousand people died—every last person except one drunk in the jail cell.

Down on the promenade I can hear the Zouk music thumping. Today is May 8th, the anniversary of the eruption. Afternoon light gilds the town, and the sailboats speckle the blue bay. Gauguin’s paradise is still here.

CRUISER RESOURCES

Marin’s Yacht Harbour Marina

Le Cul-de-Sac Marin bay (southern Martinique)

Tel.: +596 596 74 83 83

Email: port.marin@wanadoo.fr

-Customs clearance is accessible on computers in marina office (customs office hours 7AM-12:15PM, tel. 05-96-74-91-64)

NOTE: Half a dozen small marinas can be found around Martinique such as the Somatras Marina (tel. 33-596-71-41-81) and Marina La Nepture [no contact info available] in Fort-de-France Bay. There are also many outstanding anchorages. Consult the most recent update of your preferred cruising guide.

Words & photos by Jad Davenport, Southern Boating Magazine March 2017