Bonefishing in The Bahamas

For avid anglers, stalking “phantoms” aka bonefishing in The Bahamas is one of the most challenging and rewarding of all fishing adventures.

Bonefishing is an experience The Bahamas intends to protect and preserve for generations to come.

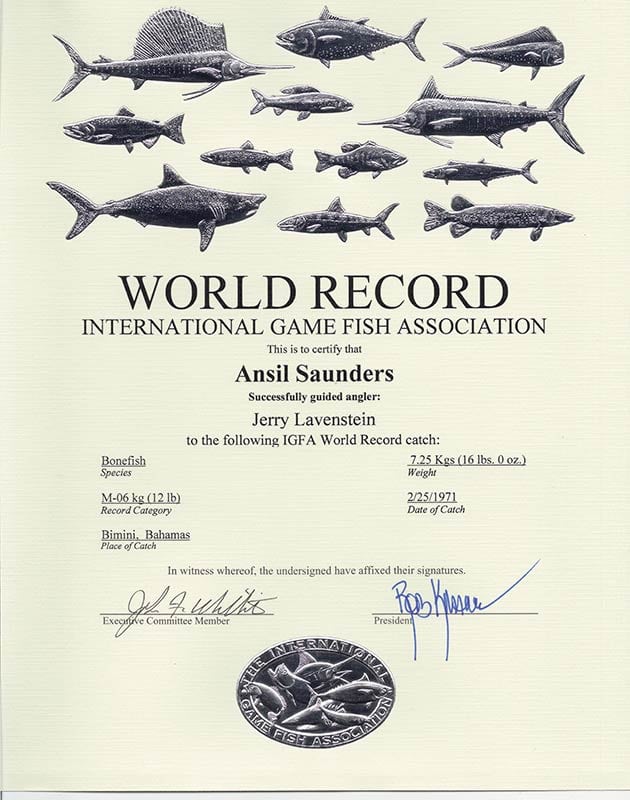

It was 45 years ago, when Jerry Lavenstein, a Virginia Beach sportsman, and his Bahamian guide Ansil Saunders headed out on the Bimini mud flats to cast their luck and chase some bonefish. Waiting silently in the gin-clear waters were small schools of the wily Grey Ghosts that have long frustrated saltwater light tackle and fly fishermen with their stealth, smarts, and speed from Grand Bahama to Abaco and Great Inagua.

Stalking bones in “skinny water” is an art—part patience mixed with technique and an eagle-eyed guide that can pole the angler close and not spook the prey. The rest is up to the fishing gods and some good luck.

Lavenstein and Saunders hooked onto immortality that day in 1971 with a record catch, a 16-pound monster, caught just 300 yards from the docks of the historic Big Game Club in Alice Town on Bimini—the largest ever landed in The Bahamas and Florida and still a species in the all tackle and men’s 12-pound line test world record.

Anytime’s a Good Time

Steve Riely, managing director at the Bimini Big Game Club, describes the island’s bonefishing as “good the year-around,” drawing both individuals and groups, many returning over the course of decades to fish with a cadre of veteran, independent local guides.

Anglers primarily from the U.S., Canada and Europe are drawn by the tens of thousands for the unique, heart-pounding challenge of hooking into a silvery fish that can reach nearly three feet and weigh in at a dozen pounds or larger.

The larger and Family Islands along with hundreds of smaller cays are good hunting grounds for the elusive bonefish, which represents an estimated $160-plus million annual economic impact to The Bahamas, providing fly fishing lodges, independent guides, local businesses, and tourism travel agents with a growing cottage industry that features a viable trickle-down benefit for the local communities.

Economic Importance

For the Bahamian economy, with an estimated GDP of about $8.4 billion, tourism accounts for some 60 percent, and the bonefishing industry segment in some cases can represent 60 to 70 percent GDP of some of the smaller out islands that rely on flats fishing and diving.

How valuable is a bonefish? Well, the market price will fetch you approximately $10, however, some experts say that same fish’s tourism value weighs in at a hefty $10,000 for the economy—as long as you catch and release.

Since 2009, The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust has been researching bonefish in Bahamian waters having tagged 11,000 of which 600 were recaptured and released, providing important data on spawning and migratory habits. “We were surprised to learn that 72 percent of those tagged bonefish that were recaptured were caught less than a mile [from] where they were originally caught,” said Justin Lewis, Bahamas initiative manager for The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust. “With that said, we have also found that some bonefish have traveled long distances for spawning—one in particular swimming from south Abaco to north Grand Bahama, a 146-mile one-way trip.”

Researchers have identified five spawning sites around The Bahamas near deepwater drop-offs. These full moon mating gatherings continue to replenish what Lewis calls a “healthy fishery” that offers anglers year-round fishing. “The goal of our long-standing research effort is to provide the information about bonefish and their habitats that is necessary to formulate an effective, comprehensive conservation strategy that focuses on habitat conservation, education, and appropriate regulation,” added Lewis.

Conservation

Vaughn Cochran, co-owner of the Blackfly Lodge in Southern Abaco, concurs. “Our waters are clean, healthy with great water flow, and the schools of various species are benefiting from the nearly pristine state of the habitat. But that didn’t happen by accident. It’s the result of good conservation practices and active research,” said Cochran. “Bonefishing the flats may be described as a unique business platform but certainly one that’s full of adventure and adrenalin for everyone involved.”

One of The Bahamas most productive bonefish habitats, the Abaco flats fishing is big business for lodges and their employees and a good living for some 50 guides. In some locations, the business passes down from father to son.

Does the industry require some government tweaking? Folley would agree that education for new guides and the local citizenry would be wise. “There are so many in The Bahamas, especially the school-age students, who would benefit,” he said.

Ronnie Sawyer’s father, Joe Sawyer, was the first bonefish guide in the Abacos. Ronnie found a sweet spot near Green Turtle Cay, where he guides for the Green Turtle Club. The man that Captain George Poveromo described as “knowing more about bonefish than bonefish themselves” is these days, working two boats depending on where the customer would like to fish. “Business is good, the habitat is good and my clients are catching fish,” said Sawyer. His business is 70 percent of return customers.

Regulations

With business seeming to be doing well, the bonefishing industry stakeholders are wondering why bonefishing has been targeted for new government regulations. In 2015, the industry took sides and became embroiled in proposed government legislation—the Fisheries Resources (Jurisdiction and Conservation) Act that some saw as a surreptitious bid to remove non-native fishing lodge management, to overregulate the bonefish industry and to create a seemingly endless pool of operating cash funded by foreign anglers.

Supporters of the act, such as the Bahamas Fly Fishing Industry Association (BFFIA) say through the legislation they are seeking to establish professional standards for all Bahamian guides, to become more involved in conservation interests and to establish a conservation fund, with a percentage underwriting the BFFIA. Many guides and lodge owners call the legislation a shortsighted path to destruction.

When will the contentious Fisheries Resources Act come before the Bahamian Legislature for formal review? According to Rena Glinton, permanent secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture & Marine Resources in Nassau, a date has yet to be set. “The proposed regulations are still under review as we seek to address concerns of all stakeholders,” she said. There will be no great impediment to persons who currently travel to angle in our beautiful waters. The focus of this ministry is to ensure the sustainable management of the fisheries and the protection of the environment. Additionally, any licensing proposal will be in keeping with current industry standards.”

Shallow Waters, Deep Roots

Clint Kemp, whose Bahamian roots date back to 1690, has fly fished the flats since age 12 and has guided for the last 10 years. Like many of his contemporaries, he agrees that change is coming. “The industry does need regulations with licenses, protection from overfishing, and enforcement of current laws that ban netting and commercial sale of bonefish,” said Kemp. “Some of the more extreme proposals to ban DIY fishing and forcing anglers to use guides should be deleted.”

“The bonefish population in The Bahamas is healthy,” says Benjamin Pratt, senior manager at the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism. However, he acknowledges some areas are fished more frequently than others.” Pratt says the BTT had collaborated with guides on Abaco, Grand Bahama, Eleuthera, and other islands and are “doing a great service to help preserve the flats habitat for bonefishing and other flats sports fishing species.”

Fishing guides by regulation must be Bahamian citizens and carry a Class B Captain’s License. That designation, however, stops so-called guides with neither skills nor knowledge from providing services.

In response, the BTT and the Fisheries Resources Act have called for an education program that would require new guides to attend a comprehensive training program. That program would include marketing, business planning, fishing etiquette, safety, and equipment maintenance. For established guides, training and refresher courses on proper handling techniques would be required. Also recommended is a comprehensive curriculum for Bahamas schools.

The Bahamas does not currently require a fishing license, “a bone of contention” for activists and conservation groups. They’d like to implement a program where license fees would be applied toward conservation of bonefish habitats, education, fishery and habitat management, and enforcement of regulations. The center of concern is exactly how those conservation funds will be managed and dispersed.

Flats Forever

Both Bahamian-owned bonefish lodges and those with foreign investors and partners are, according to the BTT, “the strongest stewards of the resource, going to great lengths to protect their fishing areas, the gamefish and the ecosystem as a whole.”

The bonefish fishery in The Bahamas, based on years of collaborative input from lodge owners and guides, is similar to the success of flat fisheries in other locations, including Belize, Mexico and Cuba. Many say the future of the fishery is dependent upon following this model.

With some 250-300 licensed guides in The Bahamas, the industry seems to be able to produce a decent livelihood for both independents and lodge-affiliated. Typical guide rates run from $400-plus for half-a-day to $600-plus for a full day.

“I can’t really see myself doing anything else,” said 59-year-old Sawyer after a morning of poling a customer along the expansive Abaco flats along the Marls on a windy February day. “I’ll be out there on the water until I can’t do it anymore. It’s in the blood.”

By John Bell, Southern Boating