What’s the difference between El Niño and La Niña?

Long before meteorologists “discovered” the El Niño (EN) phenomenon, fishermen in Chile and Peru were well aware of it. Typically, the fishing there was great. The deep, nutrient-rich waters attract bountiful marine life, but every few winters, things would change dramatically. It got much warmer, it would rain in the coastal desert region and the fish would leave. A flood of warm water from the west would push the bountiful cold water to the south. Since this was often most pronounced around Christmas, they called it El Niño for “the boy.” La Niña (LN) is the female equivalent.

The Boy and the Girl

The El Niño and its counterpart, La Niña, have major impacts on the weather around the world, but did you know they are actually oceanic circulations? To explain the EN/ LN cycle, one must go to the tropical Pacific Ocean. With the cold Humboldt Current and associated upwelling, the eastern Pacific waters off of South America are abnormally cold, over 10ºF colder than sea surface temperatures in the western Pacific. In the tropics, the prevailing (or trade) winds tend to blow from east to west and drive the ocean surface waters with them. The North Equatorial Current flows westward from the South American coast across the Pacific to Oceania in the Asia-Pacific region.

There are times when the trade winds weaken and, consequently, so does the equatorial current. Warm water, which used to be transported across the Pacific, now begins to “back up.” Water temperatures then begin to abnormally rise in the central Pacific and work its way back to the South American coast. This warming can amount to a two- to six-degree increase over normal conditions, a significant departure for this vast amount of water. This is the El Niño.

With La Niña, the trade winds and equatorial current are abnormally strong. Larger than normal amounts of warm water is transported away from the central and eastern Pacific, and water temperatures there become unusually cool. Both El Niño and La Niña events tend to develop in the spring, hit their peak intensity in the winter, then weaken the following spring, about a 9- to 12-month average lifespan.

Cycle(s) of life

Meteorologists often refer to the EN/LN cycle as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The Southern Oscillation deals with the atmospheric pressure changes in the Pacific region that accompany the two phases. In addition to the two extremes, we can have more average conditions (called ENSO neutral).

So, how and why does the EN/LN cycle affect our weather? The tropical oceans are a vast storehouse of heat or energy. They transfer some of this energy to the air which goes high into the atmosphere and “feeds” powerful jet streams. Changes in the tropics can reach well into the mid and high latitudes.

The effects of the EL/LN cycle are most pronounced in winter. The warmth of El Niño fuels a strong, southern jet stream that starts in the eastern Pacific and produces an active southern storm track that blocks cold air from entering much of the U.S. Thus, we can expect northern tier states to be warm and relatively dry, the south having normal to cool temperatures and wet from southern California to the East Coast. In a La Niña event, the energy is concentrated in the western Pacific basin.

In this Hemisphere

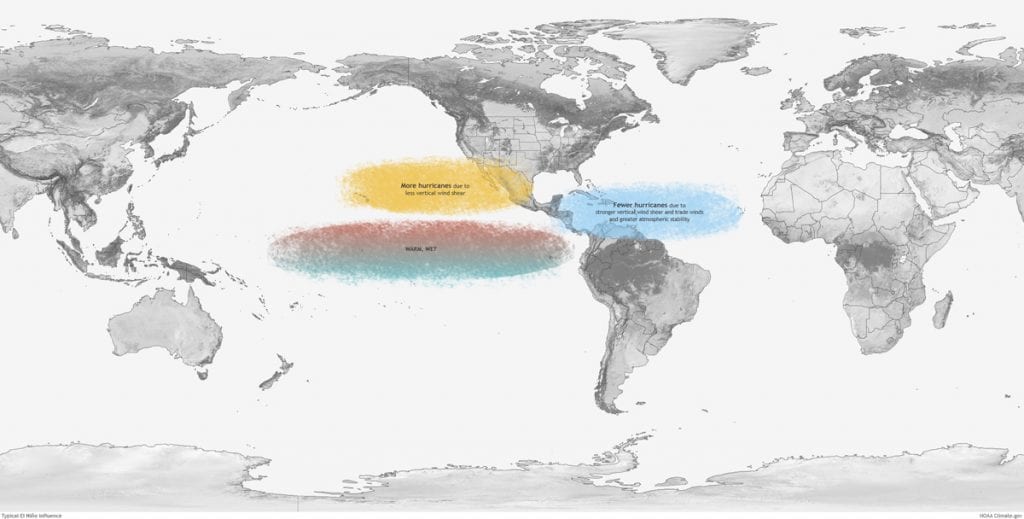

For North America, La Niña brings a more variable northern jet stream and a northern storm track with occasional cold outbreaks. La Niña tends to bring warm and dry conditions to the south with cooler and wetter conditions to the north. Although the EN/LN cycle is less of a weather controller in summer, there is one important effect—El Niño summers tend to have fewer Atlantic hurricanes due to wind shear because of relatively strong westerly winds aloft in the tropics. Conversely, La Niña years see less wind shear and increased tropical cyclone activity.

You would think that because of its influence and possible major impact on winter weather, the EN/LN cycle would be a great forecasting tool for meteorologists. Yes, it’s often the basis of winter forecasts, but it’s not so simple. By closely monitoring ocean temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific, meteorologists can typically tell when one phase or the other is beginning, and because it takes months to achieve maximum strength, they can give advanced warning, but the EN/LN cycle is not a regular occurrence.

An El Niño event is not necessarily followed the next year by a La Niña. The return period on the cycle varies from two to seven years, and the strength of the actual event varies considerably. There are also other weather influences that can override the El Niño or La Niña effects, and these other factors can’t be forecasted months in advance.

Current State

The winter of 2015-16 saw the strongest El Niño on record and was the first El Niño since 2009-10. This was followed by weak La Niñas the next two winters. In 2018, fall saw tropical Pacific Ocean temperatures running above normal, and it appeared that an El Niño was developing, but it’s a weak one. The official winter forecast (Dec-Feb) reflects this with only the southeastern part of the country predicted to have near normal temperatures and the rest a bit warmer. Wet conditions are forecasted for the southern tier states, while the north is expected to be normal to dry.

You may wonder what causes the EN/LN cycle. Well, we don’t know. Does climate change affect the cycle? Probably, but it’s hard to prove. It’s speculated that the EN/LN cycle has been going on for thousands of years and, most likely, will continue for many thousands more.

By Ed Brotak, Southern Boating January 2019