South of Havana and the visiting hordes of Americans, Cuba offers a wilderness that even a half-century of revolution left unspoiled.

I spot the flamingos as I paddle my sea kayak around a corner in the coffee-colored lagoon. There are about a hundred birds along the mangrove shore, and it’s so quiet and I’m so close that I can hear their gurgled chuckling as they high-step through the shallow water. I remember what a taxi driver told me when I first arrived in Cuba and asked how far you had to go from Havana to really get out into Cuba. He laughed. “You don’t have to go very far in Cuba to go very far in Cuba.”

I’m on a weeklong sea kayak expedition with ROW Adventures (cubaunbound.com) along the southern coast of Cuba. They’ve promised me a chance to get off the tourist-packed streets of Havana and experience the island beyond frozen mojitos and joyrides in vintage Chevys. And now, halfway through our journey, Havana feels as far away as Miami. It’s just me, the muddy labyrinth of mangrove channels, the gorgeously delicate birds, and the misty blue mountains of the Sierra Escambray rising beyond.

Soon the spell is broken by the hollow thump-thump of paddles against plastic kayak hulls and the happy conversations of my fellow paddlers. The shy flamingos launch into a low, lazy flight and blur past me in a peach-sherbet smear. They climb, circle our boats once and vanish beyond the next bend somewhere deeper in the swamp. I lift my paddle and dig into the water. I’m only a half-mile into today’s five-mile paddle, but already my face hurts from smiling so hard.

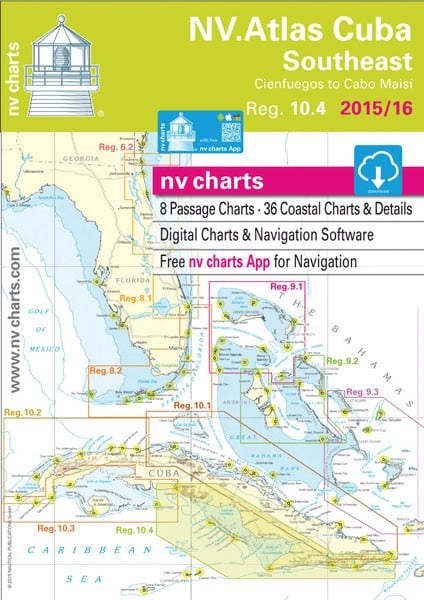

Cuba travel restrictions for Americans relaxed a few years ago under the Obama administration, though rules on traveling there by boat were slower in coming. Now, cruisers (and kayakers) have fewer restrictions but are wise to consult with an experienced agency for the requirements to visit this North Korea of the Caribbean by boat. (See the resource list at the end.) It’s safe to say there is a mad rush to Cuba going on right now. In 2016, the island saw over 3.5 million tourists, with over a million visitors in first four months. “We have a joke here,” a taxi driver tells me. “All the Americans are rushing to see Cuba… before all the Americans rush to Cuba.”

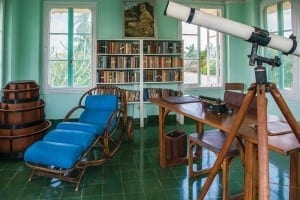

After an obligatory tour of the capital and Hemingway watering holes, our group hops a brand-new Chinese tour bus and heads two hours south to Playa Larga, a small fishing village on the Zapata Peninsula. It’s a quiet town barely two streets deep from the beach with just a few rows of red-roofed pink shacks. Horse-drawn carts drop students off after school, and men mend fishing nets in the shade of coconut palms. There aren’t any hotels in town yet, so we’re split up into private homes. Shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba descended into an economic crisis, and Castro allowed individuals to rent out rooms in their homes as “casa particulares,” quasi bed-and-breakfast establishments. Mine, the Casa Tiki, is clean, the bedroom kept polar by an air conditioner and rotating fan; my private bathroom is shiny and smells of bleach.

Later that afternoon, Lerdo, our local kayak guide, leads us out of the bay. Miles of mangrove swamp line the scooped coast, broken here and there by the white flash of beaches. “Back in the 1700s, these forests were full of wild boars,” he says. “So the French sailors started a trade. They shot the pigs and cured the bacon on wooden racks called boucans. But the traders refused to pay tax to Havana and were considered outlaws. They were called boucaneros.” Lerdo waits hopefully for one of us to make the connection. “Pirates!” He finally says. “You’re in the bay where the word buccaneer was born!”

It’s a fun bit of trivia, but the rest of the world knows the bay for another reason. On April 16, 1961, more than 1,400 mercenaries trained by the CIA landed here in the Bay of Pigs and tried to lead an uprising. Lerdo ticks off the beaches as we pass them: Blue Beach, Green Beach, Red Beach. As the surf picks up, we tuck in closer to shore. A small resort fronts one of the landing zones. A couple of guys are trying to get a surfing kite airborne, while a Swiss couple snorkels out to say hello and ask if we’re Americans. Children splash in the waves.

The invasion failed, Lerdo says, sticking close to the official account of a heroic resistance and a united people. The invaders who weren’t killed were taken prisoner, and eventually swapped in a political exchange. The only reminder left of the invasion today are the miles of ragged coastline, still as wild as they were back then.

Playa Giron is poised to become famous again—not for an unsuccessful imperial invasion but as the gateway to the Caribbean’s last truly unspoiled wilderness. The next morning we drive down a sandy arrow-straight road deep into the heart of the Zapata Peninsula, Cuba’s largest national park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was declared a national park back in 1936.

We spend all day paddling a glorious sky-blue lagoon so bright it hurts my eyes even with sunglasses. We paddle past islands of palmettos and tangles of mangroves. Rosette spoonbills step daintily among the shallows and white egrets probe the mud for crabs. Large schools of bonefish stir up the milky water. The sea is shallow, rarely more than a meter deep, and often my keel scrapes the sandy bottom. We’re the only ones in this vast wilderness today, maybe the only ones here this week. I learn later that more people summit Mount Everest every year than kayak the Zapata Swamp.

Over the week, we make our way ever eastward through the Zapata Swamp, through the lagoons around Cienfuegos and along the rugged cliffs off Trinidad. Near the end of the week, we reach our terminus at Cayo Blanco, a small crescent island. We can’t reach it by kayak since it’s nine miles offshore and the waves are too steep. So we take one of the rare motorized boats available from a marina outside the colonial town of Trinidad. Our Cuban escort can’t join us. Why not, I ask. He shrugs. “Cubans need a special permit to ride in a motorized boat. And I don’t have a special permit.”

The open sea is choppy and people are seasick. When our captain spots a fleet of wooden sailboats fishing a nearby bank, we detour out. There’s a shouted exchange as the fishermen sling three red snappers aboard and the captain tosses back two liters of cola.

We land on the island. Anywhere else in the Caribbean this sugar-sand beachfront would be lined with high-rise resorts and studded with candy-cane beach umbrellas. But here there’s only a small government-run café powered by about 40 car batteries hidden behind the kitchen. Sunburned Brits line up at the bar for rum over crushed ice, while large Russians stall out the buffet line as they carefully pick all the lobster bits out of the soggy, communal paella.

I’ve gone as far as I’ll go on this journey through Cuba. On our homeward journey, I climb to the bow. The emerald water rushes beneath my bare feet. Far ahead the mangroves guard the shore. Beyond them climb the Sierra Maestra. The horizon to port and starboard is empty, just endless green waves heaving under a blue sky. A tern drops in and keeps pace with the boat. And for the moment at least, while the rest of the paddlers’ nap in the shade of the bridge, Cuba all around me is wide and open and unbound.

— Story and photos by Jad Davenport, Southern Boating Magazine February 2017

cruising to Cuba resources

Cuba Seas

cubaseas.com

International SeaKeepers Society

seakeepers.org/cuba